http://suedafrika.habitants.de/?p=15

http://german-development-cooperation.org/files/coalface.pdf

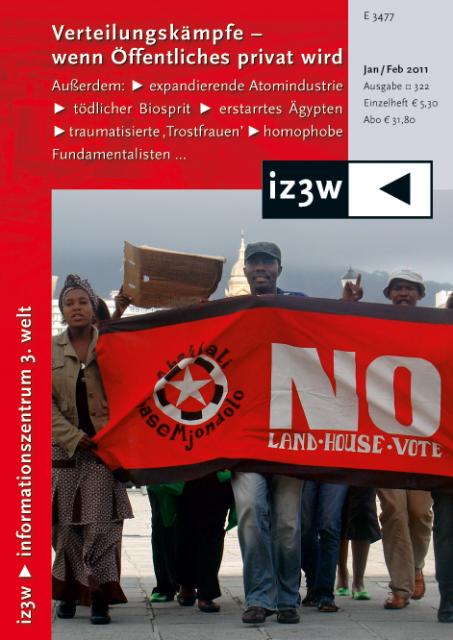

Abahlali baseMjondolo – how a poor people’s struggle for land and housing became a struggle for democracy

by Gerhard Kienast

Over the last couple of years, Abahlali baseMjondolo (AbM), an organisation of shack-dwellers from Durban, claimed some remarkable victories for participatory democracy. In 2006, using the Promotion for the Access to Information Act, AbM compelled their municipality to disclose plans for the city’s informal settlements and its housing budget. In February 2009, after tough negotiations with eThekwini, they reached agreement that the ‘clearance’ of the ‘slums’ they live in, would follow principles of in situ upgrading rather than relocation outside city limits. In October 2009, the Constitutional Court upheld AbM’s application that the Kwazulu-Natal Slums Act invited arbitrary evictions and thus declared it unconstitutional.

Yet, the movement’s latest victory was announced in the hour of its greatest affliction. On 26 September, AbM’s strongest base, the Kennedy Road settlement, was attacked by armed militia, apparently acting with the support of local ANC structures. In the aftermath, houses of AbM supporters have been destroyed, 13 members imprisoned and death threats forced its leaders into hiding (see article ‘The attacks on Kennedy Road’). Amnesty international has expressed concern over “the apparent unwillingness of the relevant authorities in investigating these crimes” and official comments, which “could have the effect of inappropriately criminalising a whole organization and making its members vulnerable to threats of violence”.

How comes that a social movement, which has merely used the freedoms guaranteed by the constitution, has attracted so much hatred? Why is it not protected by the State, which is supposed to defend the same freedoms?

Popular social movements like AbM, the Landless People’s Movement in Johannesburg and the Anti-eviction Campaign in Cape Town pose a serious challenge to the ruling party because of their refusal to vote. Since they adopted the slogan ‘No Land! No House! No Vote!’ they have been subjected to all kinds of state repression, ranging from the ban of marches to illegal police assault and detention.

AbM’s radical position did not emerge overnight. For years Kennedy Road had sent representatives to meetings with government. Confrontation started in March 2005 when shack dwellers found out that land they had been promised by their ward councillor and senior officials was developed for a brick-making factory. People embarked on road blocks and mass demonstrations, which soon gained support from other settlements across the city. ANC and government officials reacted angrily. Some suspected opposition parties to incite the poor; some blamed academics at the University of Kwazulu-Natal (UKZN); others spoke of a ‘Third Force’.

In November 2005, S’bu Zikode, the elected chairperson of Abahlali baseMjondolo, responded to these accusations in a newspaper article, which drew enormous attention as it was re-published by mass market magazines and quoted on South African television as well as by the New York Times, the Economist and Al Jazeera:

“The Third Force is all the pain and the suffering that the poor are subjected to every second in our lives. … Those in power are blind to our suffering. … My appeal is that leaders … must come and stay at least one week in the jondolos. They must feel the mud. They must share 6 toilets with 6 000 people. They must dispose of their own refuse while living next to the dump. … They must chase away the rats and keep the children from knocking the candles. They must care for the sick when there are long queues for the tap. … They must be there when we bury our children who have passed on in the fires, from diarrhoea or AIDS.”

Over the years, many intellectuals assisted the shack dwellers movement but it is a misconception that they have formed it. One of the first who went to Kennedy Road and got involved was political scientist Richard Pithouse: “The key factor (for the movement’s success) is that Kennedy Road had developed a profoundly democratic political culture and organization, years before they blockaded the road.” Until 2005, many who later joined AbM were organised in ANC structures. Initial protests were not intended to trigger a break from the ruling party. Pithouse is sure: “The radical opposition was forced on the activists because the party responded with police force instead of engaging with their demands.”

Impressed by the integrity of Sbu Zikode and other shack dwellers and the ideas they expressed, people like Pithouse helped them get in contact with human rights lawyers who would defend those arrested during the protests, and the Freedom of Expression Institute, which asserted their right to march.

The main demand of the movement was always land or housing close to working opportunities, schools and clinics. Assisted by the Cape Town-based NGO Open Democracy Advice Centre (ODAC), AbM used the law to get access to the official plans for their areas. Plans confirmed that the municipality basically aimed at the demolition of shacks and people’s relocation to the periphery. The threat of eviction mobilised even more people to support the movement.

Since their ward councillor wouldn’t resign, shack dwellers effectively started to govern themselves and gradually gained recognition by government departments. The Kennedy Road Development Committee started to issue letters confirming residence, which are needed to access social grants. AbM managed to marginalise politicians and negotiate directly with state officials about the installation of public toilets, issues of policing and disaster relief after shack fires. Clearly, this was made possible by the pressure created through mass mobilisation and skilful media work.

Repeated arrests and police violence against the movement’s leaders, evictions and fire disasters in several shack settlements did not break its momentum. Throughout 2006 and 2007, AbM organised marches against the Ethekwini municipality, which privileged middle class housing, office and entertainment parks. Faced with shack dwellers’ determination and growing embarrassment over the fatalities caused by shack fires, the Metro started to negotiate.

Project Preparation Trust (PPT), a service provider facilitating housing projects on behalf of government, was mandated to find a consensus. AbM seized the opportunity but did not compromise its commitment to grassroots democracy. When PPT requested the nomination of two negotiators, this was rejected. Abahlali insisted that each of the 14 affiliated settlements could send 2 representatives. Representatives had no mandate to make decisions during negotiations. Hence, each proposal had to be brought back and discussed in the respective community. AbM even sent ‘less prominent’ people in order to broaden the knowledge about the process. For political scientist Pithouse this is fascinating stuff: “AbM deliberately works with a delay through participation. They embark on ‘slow politics’ to ensure that all members of the community are part of decisions.”

By February 2009 an important breakthrough was reached. AbM and city officials agreed on the modalities of in-situ upgrading, and on alternative housing for shack dwellers, which could not be accommodated within the parameters of the existing settlements.

Yet, negotiations with the municipality did not prevent the movement from mobilising against provincial legislation, which was undermining shack dwellers’ tenure security. The ‘Kwazulu-Natal Slum Elimination and Prevention of Re-emergence of Slums Act’ of 2007 gave the housing MEC powers to force landowners and municipalities to institute eviction proceedings. AbM had requested participation in the public hearings on the bill but its submissions were dismissed (along with many others). When the law was enacted, AbM launched a legal challenge to have the act declared unconstitutional.

In October 2009, the Constitutional Court found in its favour and ordered that all costs of AbM’s court applications be carried by the Kwazulu-Natal government. The judgement underlines that “eviction can take place only after reasonable engagement … Proper engagement would include taking into proper consideration the wishes of the people who are to be evicted, whether the areas where they live may be upgraded in situ; and whether there will be alternative accommodation.”

Housing expert Marie Huchzermeyer of Wits’ School of Architecture and Planning whole-heartedly welcomed the judgement. In an article for Business Day newspaper she explained: “(Section 16 of the act) harked back to a provision in the 1951 Prevention of Illegal Squatting Act. … It was a very worrying regression in law that needed to be challenged.”

AbM president Sbu Zikode, still in hiding after the attacks on his Kennedy Road home, had reason to be proud after the court decision. In the Mail & Guardian he said it “had far-reaching consequences for all the poor people in the country and validated ABM’s role as protector of the Constitution, and a champion of the rights of the ordinary people of South Africa. … Hopefully, this judgement will also see the end of forced removals to transit camps and temporary relocation areas.”

But what will become of the agreement reached with eThekwini now that over 30 activists’ houses were destroyed and dozens, some say hundreds of families were driven out of their homes? As long as many AbM activists remain homeless and are living under death threats, this seems to be quite an irrelevant question. According to Richard Pithouse “the movement is now operating underground in some areas and, due to the enormous pressure it is now under, struggling to sustain its practice of open and regular meetings.”

In a panel discussion on human rights activism and litigation, Stuart Wilson, visiting senior research fellow at Wits Law School, pointed out the significance of their persecution: “… we have a Constitution which, at least formally, guarantees the inclusion of all in the political community. But democracy must also fill the spaces between the elections. The freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution must be practiced – and permitted to be practiced by the citizenry. The attack on Abahlali is an attempt to stamp out that vital practice of democracy.”

The attacks on Kennedy Road and the call for an independent inquiry

On the night of September 26, 2009, two weeks before the Constitutional Court decision on the KZN Slums Act, an Abahlali meeting in Kennedy Road was attacked by a group of armed men, chanting ethnic slogans and threatening to kill the movements’ leaders. Residents fought back and two people died under unknown circumstances. The next day the attacks continued. According to several witnesses they were carried out by supporters of the ruling party. With the ward councillor and the chairperson of the local ANC branch standing by, they destroyed and looted the homes of 30 well known AbM members as well as the movement’s office and library.

Stuart Wilson of Wits Law School recounts what was said by neighbours: “The police were present and did nothing to stop the pillage. They only intervened to arrest members of Abahlali who resisted the gang. Many other families associated with the movement fled in fear of their lives. On Monday morning, the local ANC councillor Yacoob Baig and the MEC for Community Safety, Willas Mchunu, arrived at the settlement, congratulated the community on having removed what they called a criminal element and declared that the community could now live in peace and harmony. Abahlali’s office was ransacked.”

One of the first prominent voices to speak out against the attacks was Bishop Rubin Phillip, the head of the Anglican diocese of Natal: “The militia that have driven the Abahlali baseMjondolo leaders and hundreds of families out of the settlement is a profound disgrace to our democracy.” Comparing the attacks to those unleashed by apartheid, he goes on: “Once again we in the churches are looking for safe houses for activists, accommodation for political refugees who have fled with nothing more than the clothes on their backs, doctors for the injured and lawyers for the jailed. … I will take my anger and my fear for the future of our democracy to the highest levels of leadership in our country and to our sister churches around the world. I encourage others to do the same.”

Since then, church leaders from various confessions have shown solidarity with the 13 AbM members who have been arrested in relation to the attacks. They have been shocked to see that the intimidation of the movement’s supporters even continues in the court room. Reverend Mavuso Mbhekeseni recalls: “The ANC mob was swearing at us in court … They threatened to catch us and kill us in the city … it was clear that their threats were serious”.

After two months in detention all charges were dropped against one of the thirteen, seven were granted bail. The other five, however, were remanded in custody to give the police more chance to bring some evidence against them in court. Their bail application has been postponed eight times (for four months!), leading Bishop Phillip to call this case a ‘travesty of justice’.

Highly-regarded international intellectuals like Noam Chomsky, Naomi Klein and Slavoj Zizek signed a petition that condemns “any participation or collusion of the government and police in the recent assault” (see text box). Amnesty International raised its concerns with the Premier of KwaZulu-Natal and has issued “repeated calls for an independent and impartial commission of inquiry into the surrounding circumstances and extent of the violence and its aftermath” (http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/info/AFR53/011/2009/en).